Growing up in Southern California, I didn’t see any Civil War statues or Confederate flags. I didn’t understand why there were still contentious debates about flags and statues. Sure, I learned about the Civil War and slavery in High School, but the arguments presented by the “lost cause” crowd muddied the truth. It was about states’ rights, they argued. But I never understood why people 150 years later felt the need to defend the Confederacy or justify its actions, regardless of what they claimed the war was fought for. I didn’t understand it, nor did I give it much thought until I wrote my senior economics seminar on the ratings of higher education in different parts of the United States. I noticed that most of the prestigious Universities (according to US News and World Report) were not in the south and wanted to understand why.

What started as a look into the different ratings of Universities led me down a completely different path. I started my economics research by looking at the motivations for the colonization of North America.

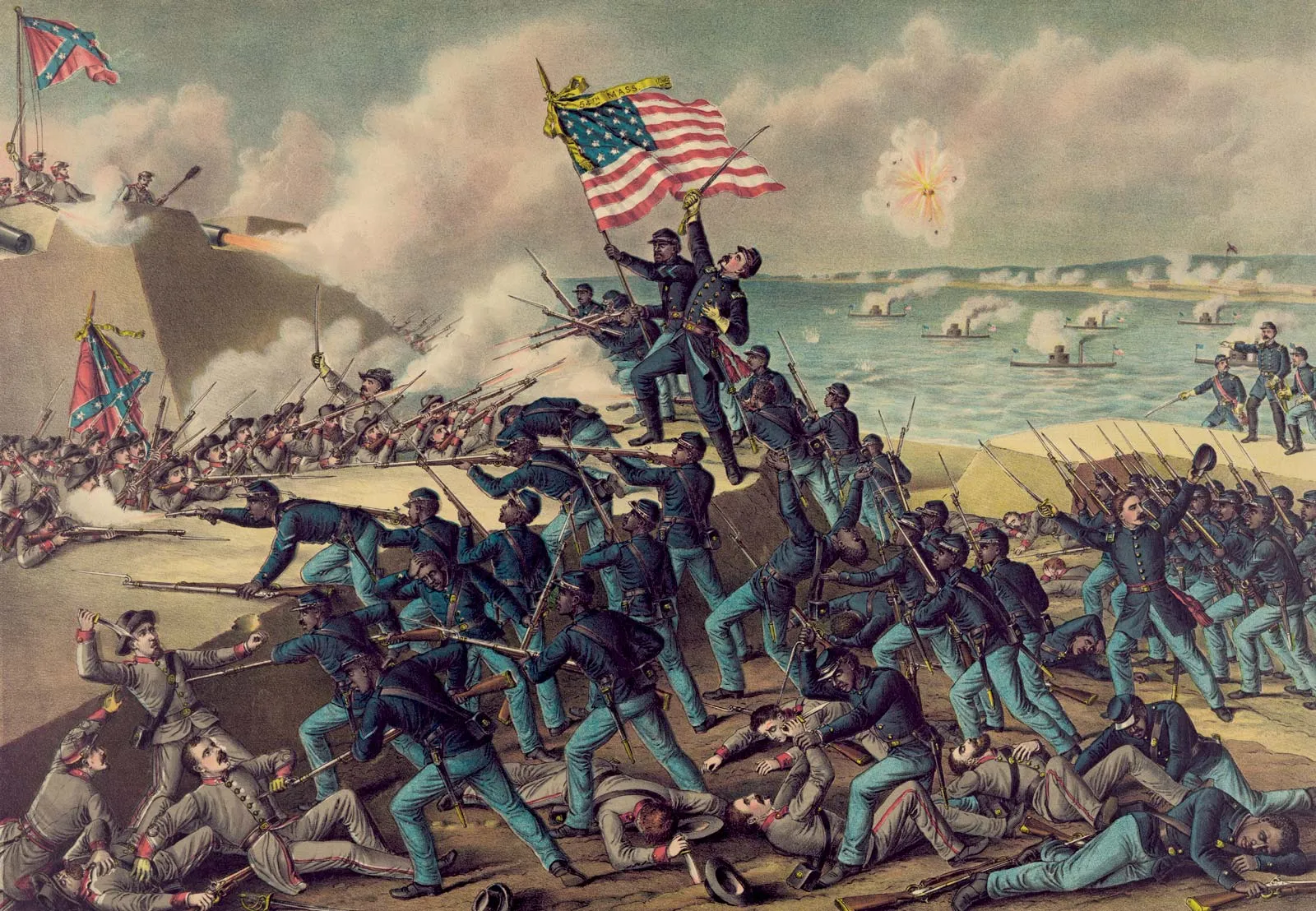

The evils of slavery, and the evils that followed it, weakened the United States tremendously both before and after the Civil War – in addition to the war itself. More Americans were killed and most of its territory destroyed by the Confederacy than any other enemy force in history. The territory of the nation would undoubtedly be larger if manifest destiny had not been tempered by the struggle to restrict slave state representation in Congress. The United States would be more populous and more prosperous today if we hadn’t embraced slavery or continued beating down our fellow countrymen and human beings in the decades that followed. We spent too much time fighting ourselves when we could have been working together to build a better America for all.

What’s more, it was all done for one single purpose: to preserve slavery. Anyone who believes the Confederacy was formed for any reason other than to preserve slavery is either ignorant or a fool. I admit I was once ignorant. It’s ok to be ignorant, but it is not ok to be a fool who would think it acceptable to justify slavery or the injustice of other men, or the lynching of men, women, and children in its aftermath.

Hundreds of thousands of southerners, many poor, were duped into believing they were fighting for their homes or their “way of life” by obscenely rich slaveholders who owned the media, government, and economics in the south, and didn’t care for the pawns they set off to war. As added insurance, many southern churches and the elite used religion to reinforce the belief that God approved of the enslavement of blacks. Others were forced to fight against their will or executed if they refused.

The planter elite who started the war certainly didn’t send their own sons off to die in a war they started, for the singular purpose of preserving their right to enslave. They could have sold their slaves to the government and remained ridiculously wealthy. They didn’t.

They could have chosen a peaceful path to respect democracy and the will of the people; instead, they chose the destruction of their own people and nation so that they could continue slavery. The confederates murdered unarmed American soldiers who had surrendered because of the color of their skin, and they refused to exchange black soldiers for white confederate soldiers. The planter elite cared more about enslaving African-Americans and keeping them as their property than they did about the white men fighting for them, many of whom would die in prisoner of war camps because the Confederacy refused to exchange a soldier for a soldier, regardless of color. This is but one example of how their deeply ingrained ignorance, greed, and hate led to unnecessary loss.

Monuments and flags of traitors and to those who fought for the enslavement of their own species should not stand as if they ever possessed a shred of honor or dignity, which they denied to those of a different color. Preserving history is no excuse; we can read about history in a book. Hitler and Stalin are part of history, but we don’t erect monuments of history to them. If we want to display our history, Frederick Douglas, Harriet Tubman, and many other true warriors and honorable people like them deserve to be recognized in place of traitors, slavers, and enemies of the United States and the values of liberty and freedom.

But what does that have to do with higher education? Well, I was surprised to learn that my alma mater, the College of William and Mary, invested its entire endowment into Confederate Bonds to finance the war, while 68 of its 70 students and its entire faculty joined the Confederate Army. Its endowment was lost at the end of the war along with most of the college campus. Who knows what that money could have built in the following 150 years.

If you’re not bored yet, I’ll share the rest of what I discovered on the education topic. Data suggest a significant disparity between the concentration of well-endowed and prestigious universities in the south compared to the north. Three main factors set the south’s higher education system behind that of the other American institutions. The history of the south’s formation, its economy, and its planter-dominated political system made higher education a low priority. Slavery exacerbated the problem, creating disincentives for investment in human capital and restricting the south’s demand for education.

The Civil War crippled southern universities by eliminating college endowments, depleting institutions of their students and faculty, and destroying educational infrastructure. The postbellum south improved its tertiary education system, but its discriminatory leanings repelled the contribution of many qualified academics.

Cultural history, slavery, and the Civil War suffocated both the south’s demand and supply for higher education, resulting in the disparity between southern tertiary education relative to tertiary education in other areas of the US.

Cultural History and Colonization

When English merchants established the first American settlement at Jamestown in 1608, they strived to expand the British crown’s economic power. Most early American settlers, particularly those in the south, were not driven by a desire for religious freedom, but rather to become rich. The south quickly developed a plantation economy centered on highly profitable cotton and tobacco ruled by a small number of elite planters, creating a stratified social structure. Southern farms were massive and plantations were widely dispersed from one another. As a result, the southern population was dispersed throughout rural areas. Consequently, the high fixed costs of establishing a university did not justify the perceived benefits, particularly since the social and economic exclusion of the majority of the south’s population prevented any such institution to capitalize on economies of scale. In addition, the planters had little incentive to invest in public education because of the high opportunity costs of diverting resources away from southern cash crops, instead, they invested most of their resources in acquiring land and slaves.

On the contrary, Puritans arrived in New England with a strong conviction for education, evident by John Winthrop, who proclaimed the colony would set an example for the rest of the world in his “City upon a Hill” sermon. To achieve this goal, all Puritans were to be educated, as reading sermons was a necessary component of becoming holy. Six years later, Harvard College was founded. In 1647, the Massachusetts colony required all towns to finance a schoolmaster to teach children to read and write. By the 1670s, all New England colonies with the exception of Rhode Island had legal provisions requiring literacy for children. The northern population was more urbanized as the Puritan settlers created socially tight-knit communities where the people lived in close proximity, allowing educational institutions to capitalize on economies of scale. The social constructs established by settlers of Jamestown and Massachusetts Bay Colonies laid the foundations for both education and the development of tertiary institutions.

While the Puritan economy in the north was based on the efforts of individual farmers, who produced a variety of crops to consume and trade, the south failed to develop a diversified economy and produced mainly cotton and tobacco. New England became an important mercantile and shipbuilding center, often serving as a trading hub. Increases in northern manufacturing and technical jobs required a more educated workforce, stimulating demand for education. Early mills and factories in New England often devoted a floor to serve as a schoolhouse. Thus, human capital did not develop in the south as it had in the north. The south had neither the supply nor the demand for higher education, particularly for the masses.

The southern plantation economy lacked a middle class and created an extremely stratified social structure. Without a middle class, the south did not have a demand for goods and services other than those that the wealthy could afford. This only served to exacerbate the southern economy’s concentration on its cash crops, resulting in a weak industrial sector and failure to provide an incentive for investment in tertiary institutions.

Formal education was common in New England but virtually nonexistent in the south. Early Puritan settlers believed it was necessary to study the Bible, and they taught their children to read at an early age, whereas southern Anglicans placed less importance on religion. Northern colonies also required each town to pay for primary school. By 1750, nearly all of New England’s men and approximately 90% of its women could read and write–rates nearly twice as high as in the south. Group schooling was prevalent in the north because it was convenient for families to send their children to a single institution in close proximity.

In contrast, southern children were homeschooled or sent to exclusive private schools, typically with a focus on agriculture. Most southerners did not believe that education had a place in the public arena and opposed public financing for educational institutions. Antebellum efforts to establish education for the common man in the south were derailed by the planter elite. They argued that in all traditional societies, the most important education one receives is in the home and that schools could never be more successful than families at educating a child. The Prussian model for education prevalent in the north was condemned by planter elites as “autocratic” and it became a patriotic duty for southerners to oppose public education, which was viewed as a threat to the southern way of life.

Southerners placed emphasis on creating a college-bred elite in order to preserve the southern way of life and to pass southern traditions to successive generations. It was common for wealthy southerners to send their children to existing institutions in the north and England, rather than invest in creating additional southern institutions, and most southern students attended private institutions. The southern majority, composed of white yeomen farmers and slaves, did not have access to higher education. In reality, elites opposed public education in order to maintain their power over the southern social and economic system; they prevented the spread of democratic principles, just as they also restricted voter eligibility. Wealthy plantation owners dominated southern politics and government revenues which could have financed education. Elite planters used their wealth to dominate the poorer whites and at election time, assumed control of local legislatures by promising to lower taxes and giving the small farmers gifts of rum. As a result, the south established a fraction of the colleges founded in the north and a small number of the southern population was educated.

Southern proponents of public education sought to follow Massachusetts’s example and consulted Horace Mann, the first secretary of the Massachusetts State Board of Education, established in 1837. During his correspondence with southern supporters of public education, Mann addressed southern opposition to public education, stating that “…colleges and academies never will act downward to raise the mass of people by education; but, on the contrary, common schools will feed and sustain the academies and colleges. Heat ascends, and it will warm upwards, but it will not warm downwards.”

While state-funded public institutions sprung up in the northern and Midwestern states in the 1840s, the south did not establish public schools “which shall be open to all without distinction of race or color, to the end that where suffrage is universal, education may be universal also, and the new governments find support in the intelligence of the people.”Although the first state universities in the US were founded in the south, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) and University of Georgia (UG), they were neither supported by strong legal provisions for state funding nor free and universal. As a result, southern society remained highly stratified, uneducated, and lacked educational infrastructure from colonization to the postbellum years, while other areas of the US enjoyed an educated populace and numerous, vibrant educational institutions.

Slavery

While cultural history retarded the southern supply of tertiary education, slavery had a profound impact on mitigating southern demand for higher education. Slavery was a highly profitable component of the southern economy and shaped economic preferences in a manner that provided little incentive to invest in human capital. Although slavery ended nearly 150 years ago, the institution of slavery and its negative impacts on tertiary education is still present. Many of today’s highest-ranked southern educational institutions used slaves in their construction, operation, and maintenance. Slavery created a massive divide between those for and those against slavery, which was “in all hearts, in all minds, on all tongues,” and “pervaded all meetings.”

Academia was not exempt from the passionate debate over slavery, which raged among and within academic institutions, including the University of Virginia, which “was created, was sustained, was energized by the institution of slavery — in its physical construction and also in its intellectual climate.” Faculty at many southern institutions demanded textbooks that reflected “southern values” and no trace of criticism of slavery.

In 1834, more than one-third of students at Amherst College in Massachusetts and several faculty and townspeople were active members of the college’s Anti-Slavery Society. While colleges in the north like Dartmouth, Harvard, and Yale eventually openly united against slavery, faculty at southern institutions who voiced even a slight opposition to slavery were fiercely denounced, blacklisted, and fired. Although there were few anti-slavery academics in the antebellum south, their punishment was rarely made public, and even fewer were published in recorded documents.

For example, in August of 1856 Professor Hedrick of UNC was attacked in the Raleigh Standard, when he acknowledged his support for the North Carolinian Republican Presidential Candidate John Frémont, the first candidate of a major party to openly oppose slavery. The article, anonymously signed “An Alumnus,” charged Hedrick with being a “black Republican” and recommended that those with “black Republican opinions” at schools be “driven out.” In his defense, and against the advice of his academic colleagues, Hedrick wrote an editorial in September, proclaiming his support for Frémont and the economic rationale for opposing slavery.

The Raleigh Standard swiftly attacked Hedrick’s article, stating that “The expression of black Republican opinions in our midst is incompatible with our honor and safety as a people…we take it for granted that Prof. Hedrick will be properly removed.” Professor Hedrick, who graduated from UNC at the top of his class in 1851 and rose to the position of Chair of UNC’s analytical and agricultural chemistry, was promptly fired by the University on October 11 on the ground that his anti-slavery views made him “unfit to be an instructor of youth.” Even after Hedrick’s removal, locals denounced him and attempted to tar and feather him outside an educational convention. Professor Hedrick promptly moved to New York and he remained in the north until his death in 1886, except for two brief visits to North Carolina. The UNC example represents a prevalent trend throughout southern institutions which lost talented academics to intolerance.

The New York Times remarked that “now an arrogant and unrelenting ostracism is applied, not only to all express themselves against slavery, but to every man who is unwilling to be the menial of slavery.” A New York Times article written in 1902 remarked that “Slavery was primarily responsible” for the south’s “unnatural burden of inherited illiteracy.” Accordingly, few northern academics chose to venture into the south for fear of similar repercussions. Clearly, intolerance over the slavery debate limited the south’s pool of qualified labor, made southern universities less diverse, and cut off a significant stream of academic capital.

Slavery also shaped the southern economic landscape and with it the south’s preferences for higher education. Slavery was concentrated in the south, largely due to the factor price intensities required for the production of cotton and tobacco, in which the south enjoyed a comparative advantage. Since nearly 60 percent of the south’s agricultural wealth was in slaves- highly mobile factors of production- there was little economic incentive to invest in manufacturing and schools that increased the value of immovable capital. The north, invested in immovable factors of production (land and factories), enjoyed a vibrant manufacturing sector and middle class which spurred demand for education. The north’s visible return on investment from human capital was not shared by the southern elites who controlled most of the wealth and invested in cotton production, which produced a highly visible return on their investment. In effect, the south’s dependency on slavery reduced its demand for education. The institution retarded the development of southern manufacturing and punished educators with conflicting beliefs, thereby facilitating an intellectual depletion and maiming the southern demand for higher education.

The Civil War

The Civil War devastated the south and flipped tertiary institutions on their heads. The southern economy was ravaged and its infrastructure demolished. Although the Civil War is typically characterized as a military conflict, it affected every aspect of American life. Colleges and universities in the north and south were called upon to contribute to the war effort. Southern institutions lost their Confederate bond invested endowments after the war, were damaged during the war’s execution and suffered from the death of a significant portion of the student body and faculty. Every southern institution either closed its doors entirely or significantly curtailed its academic activities as admission rates plunged and college-aged men filled the ranks of the Confederate and Union forces. Colleges throughout America formed their own military units, or College Companies, led by faculty and staffed by students.

At the College of William and Mary (WM) in Virginia, the south’s first institution of higher learning, most of the student body enlisted in the Confederate Armed Forces by May 1, 1861. Shortly afterward, college President Benjamin Ewell became an officer in the Confederate Army. The college ceased academic operations in October and served as a hospital and barracks for Confederate forces. This trend was common for most tertiary institutions in the south, including Emory and Henry College, UNC, UG, and the universities of South Carolina, Alabama, and Mississippi. Although most students volunteered to fight for the Confederacy in the spring of 1861, many more were forced to serve when the Confederate government passed conscription laws in 1862. More than 2,000 students at the University of Virginia fought for the confederacy, accounting for approximately 80 percent of its student body. At VMI, 94 percent of its students left their studies to serve the Confederacy, and UNC’s attendance dropped from 456 students in 1859 to 60 students in 1865. Tens of thousands of southern college students and faculty were wounded or killed during the war. Students returned to find many of their buildings in ruin, including areas of VMI, WM and Duke that were destroyed by Union forces. President Ewell returned to William and Mary in 1865 to find the school in ruin and disrepair, the main building burned to the ground and minuscule resources with which to resume operations, notwithstanding the funds required to repair the campus.

The Civil War’s impact on southern higher education would have been relatively milder if only the southern institutions had endowments left to cover reconstruction expenses and sizeable student bodies. Many southern institutions, including William and Mary, Duke, and UNC, invested their endowments in Confederate War Bonds, currency, and southern banks. When federal forces triumphed over the south, the Union chose not to assume the south’s massive debt that it accumulated to finance its war against the Union, absolutely devastating southern institutions. Some colleges closed permanently and students at many institutions paid little or no tuition. Many professors left southern academia as most colleges could not afford to pay a decent salary, resulting in either an exodus from academics or relocation to financially healthy northern institutions.

With the exception of UVA, southern institutions were slow to recover from their wartime losses. Davidson College in North Carolina, which prided itself on a $234,293 endowment in 1862, the largest of any institution south of Princeton, lost $95,100 from failed banks and worthless Confederate bonds in 1865. In 1867 Davidson suffered from a $10,000 budget shortfall that it addressed by canceling scholarships and soliciting the public for loans. The College of William and Mary was so devastated by the financial collapse that it finally resumed operations limping on a financial prosthetic in the 1870s, only to falter and suspend operations in 1881 with doubts that the institution would reopen.

Reconstruction to the Civil Rights Movement

Many historians greatly underestimate the tremendous importance of the civil rights movement and reconstruction effort in reforming higher education in the south. If cultural history, slavery, and the Civil War established southern tertiary education during the first 175 years, the reconstruction era and civil rights movement revolutionized it. For a short period following the Civil War, blacks gained political influence in the south which they first used to finance, construct, and staff schools. The southern blacks allied with Radical Republicans in Congress and others in Southern constitutional conventions to create a new framework for education. These constitutional frameworks established education as a basic right for all races and created new methods for the finance and governance of public education. W.E.B. Du Bois remarked that “the first great mass movement for public education at the expense of the state, in the south, came from negroes.” The Reconstruction conventions and state legislatures, guided by the black-Republican alliance, were responsible for establishing universal public education in the south. As a precondition for their readmission into the Union, former confederate states had to establish “public schools which shall be open to all without distinction of race or color, to the end that where suffrage is universal, education may be universal also.”

While pre-war constitutions contained vague clauses regarding education, if any, reconstruction provisions included definitive shall declarations. Most contained language requiring schools to stay open for a minimum amount of time or forfeit state aid, specified sources and levels of taxation, and specified systems of educational governance. As a result, illiteracy among African-Americans plunged from 79.9 percent in 1870 to 44.5 percent in 1990 and enrollment increased from 91,000 in 1866 to 572,000 in 1877.

These reforms increased demand for higher education in the south, which spurred an increase in the southern supply of academic institutions. As blacks became free and more blacks became literate, they demanded access to higher education. The demand was met and black colleges and universities sprung up across the south. The constitutional provisions also benefited the majority of the white population, who finally received a basic education and had greater access to college. In 1873 Cornelius Vanderbilt donated $1 Million to rescue war-ravaged Central University, which became Vanderbilt University, in hopes of healing the wounds inflicted by the Civil War, although he had never traveled to the south. However, reform efforts within reconstruction governments were short-lived, stalled by the return of weakened but powerful elite planters in the 1870s. Reconstruction failed to reform the south’s political economy. Statutes and state constitutions, once a source of hope for reconstructing the south’s social structure and education system, quickly became a method for repression and segregation. Although massive disparities emerged between white and black institutions, principle provisions regarding educational finance and the provision of universal education remained in the constitutions.

On the contrary, legal segregation was banned in South Carolina and Louisiana but remained throughout the south. The free exchange of academic talent between the south and other areas of the US remained tarnished by racism. As with Professor Hedrick, it was not socially acceptable to openly support equal rights for blacks. Black counties received little funding for education as local white officials ruled over state funding for education in black counties. A 1916 report on the funding of southern black schools found that in counties with a black student population of 75 percent or more, blacks received $1.78 per capita compared with $22.22 for whites. Accordingly, these practices also cheated poor whites outside black communities because planters from black areas fought to keep school taxes low. These provisions had a negative impact on higher education in the south, once again restricting the development of academic ability for large segments of the population and reducing demand for southern tertiary education and institutions.

The civil rights movements in the 1950s and 1960s damaged the reputation of southern universities. Many southern administrations were divided on segregation and struggled to address questions of race. Southern states opposed federal regulations mandating the end of segregation at all American institutions. In 1957 Arkansas Governor Orvall Faubus refused to admit nine black students into an all-white school, going so far as to deploy the National Guard to block their admission. Faubus was overpowered when President Dwight Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and deployed the 101st Airborne Division to protect the nine black students and integration efforts.

The combined efforts of civil rights leaders, civil rights legislation and enforcement dissipated much of the barriers restricting the demand for higher education. With integrated primary and secondary education systems, the south generated more consumers of higher education, facilitating growth in the number and quality of southern institutions. A vast portion of the southern population – blacks and whites- was finally able to flourish in a peaceful academic environment and granted access to institutions that would prepare them to enter the tertiary system. In effect, civil rights efforts removed many of the barriers to the south’s supply, demand, and development of tertiary education.

Closing

Southern cultural history, slavery, the Civil War, and the reconstruction and Civil Rights eras played an integral role in the health of today’s southern institutions and do much to explain the current geographical distribution of highly ranked tertiary institutions away from the south. Cultural history served to shape both economic and social preferences for higher education in the south. The high fixed costs of establishing an additional tertiary institution and an inability to capitalize on economies of scale due to the exclusion of vast segments of the southern population—yeomen farmers, slaves, and blacks—did not provide an incentive for the elite to expand the supply of tertiary education when they could send their children to existing institutions in the north or overseas. As a result, there was weak demand for higher educated in the south because social and economic considerations inherent in the south greatly reduced the potential consumers of tertiary education. Since demand for higher education never materialized in the south as it had in the north, a supply in the south failed to materialize and the market for higher education in the south remained weak while it prospered in the north.

Further, slavery and the south’s plantation economy created a disincentive for the ruling elite to invest in universal and public tertiary institutions that represented a threat to the posterity of their dominance over the south’s political economy. Additionally, the absence of a middle class and a subsequent market for consumer goods in the south retarded the development of its industrial sector, which created a demand for higher education in the north. In contrast to the north, the south did not need to invest in human capital to operate, maintain, and repair complex machinery in highly immovable factors of production. Rather, the planter elite was comfortable in their plantation economy and experienced a greater rate of return in expanding their cotton and tobacco operations through continued investment in highly moveable factors of production—slaves—rather than investing additional funds in southern institutions. Slavery also poisoned the heart of academic discourse and academic administrations, punishing faculty whose beliefs opposed slavery and mitigating the free exchange of academic talent and thought. The Civil War completely shattered southern institutions’ financial and physical foundations, liquidating endowments and eradicating enrollments.

Although the south’s higher education has suffered a tragic and volatile history, its prospects are stronger than ever. Thanks to reconstruction and civil rights reform efforts, southern institutions like UVA, WM, Duke, and UNC have developed into higher-quality institutions, embracing qualified persons of all races. The south has indeed risen, as its colleges and universities have emerged into competitive institutions. There is no doubt southern tertiary education will continue to flourish into the 21st century.

And there is no doubt that slavery and racism are cancer to the United States, its history, and democracy. We must never forget this dishonor and despicable aspect of America so that we may work to never repeat it or anything like it in our future.

History is free wisdom passed to us by the mistakes of those who came before us. All we have to do is listen, and act.

.

.

.

.